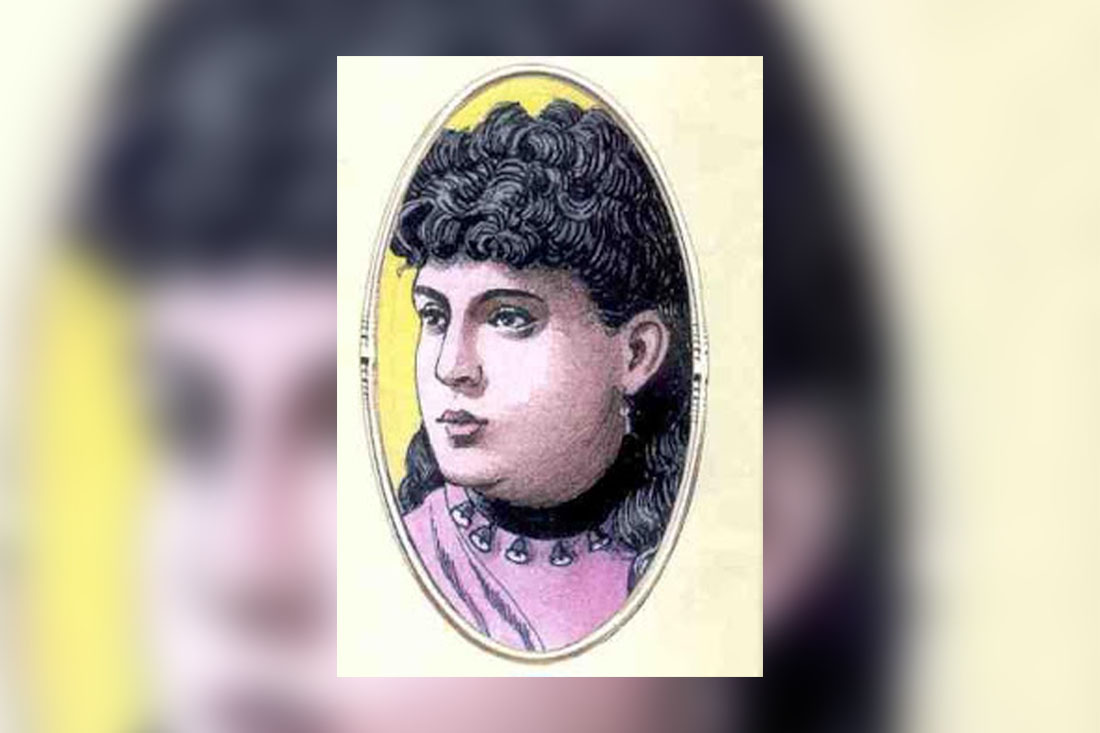

The woman within the Cuban independence process occupies a very important place, because within her right context, where the female condition limited her actions, she also knew how to give everything to the service of the country. This is well demonstrated in the figure of María de la Concepción “Concha” Agramonte Boza, a woman of proven character and libertarian demonstrations, evidenced from a very young age.

Birth and family

Concha Agramonte was born on December 7th, 1834. She was the daughter of Juan de la Cruz Agramonte y Arteaga and Doña Rufina Bozo y Varona, who were able to offer her an excellent education due to her economic position. From very early on, she stood out for her great beauty and intelligence, but also for her patriotism.

Marriage and war

At the age of 17, in 1852, she married Francisco Sánchez Betancourt, as a result of this union 12 children were born. She joined the revolution of 68, and after the incorporation of Camagüey to the war, she marches to the insurrectionary field together with her husband and her descendants. From there her performance would be admirable.

Hospitable treatment found in her house the young people from Havana: Ayesterán, Juan M. Ferrer, Moralitos, Mendoza, Julio and Manuel Sanguily, Zambrana, the brothers Luis Victoriano and Federico Betancourt, who were seeking to join the mambisas ranks. She leaves for Guáimaro, where one of her first tasks was to take care of the Constituent Assembly delegates, since various articles of the Constitution were discussed in her home. In addition to the fact that according to her own testimonies, one of the most important and happy pages of her life was having witnessed this proclamation.

Vicissitudes and exile

The evolution of the conflict itself caused Concha problems and vicissitudes. Her life, previously full of luxuries and comforts, would become marked by shock and anguish, but in order to support the independence ideal.

In 1871 she and her little ones felt their lives threaten when a Spanish force arrived at the place where they were staying. However, thanks to the benevolence of the Spanish chief, an acquaintance of hers, she obtained a safe passage of eight days so that she could pick up several of her children who, due to the confusion, had hidden in the mountains.

After different events, she arrives in New York, exile in which she will be until 1878; which will be very hard at first, due to her not being able to have the support of the her husband’s family, in addition to other inconveniences to obtain the money from an account of her spouse. But she will prevail with her intelligence and stamina once more, supporting her family as a seamstress.

Family reunification

At the end of the war, she is reunited with her husband and her eldest son, Benjamin, but with the sadness caused by the death of her other child, Juan de la Cruz. However, both consorts had performed their duty well. However, the joy would be overshadowed by the death of Francisco, after a long and painful illness.

The Necessary War

The new war does not surprise “Concha” Agramonte, who with pain and satisfaction accepts, supports the march of each of her five male children to the call of the homeland. Although with the same spirit, but with a body marked by the years, she also offers her house as a meeting place.

Through her mediation, the young people from Havana that Dr. Raimundo Menocal, a former friend of his son Eugenio, sent recommended, such as Dr. Eugenio Molinet, the Sonville brothers, Raúl Arango , Néstor Aranguren, Armando Menocal and many more were able to go to the battlefield. She also intervenes as a courier of the correspondence of those with her relatives and of information about what happened in the revolution; reason for which she suffers prison along with other respected ladies of society and was exiled again.

Back in New York, this time accompanied by her daughter, Emilia, and her daughter-in-law, Caridad, with two of her children, she does not experience the torments she had previously suffered; because the services offered to the relatives of the patriots and the communication with them were better organized. After the War of 95, she returns to meet her beloved children.

María de la Concepción Agramonte would spend her last years in Havana, surrounded by admiration and respect for a whole society that saw in her an example of the sacrifice of Cuban women for the emancipation of Cuba.

Bibliography

Peláez, Yolanda. La mujer en la Revolución. Periódico Adelante, 1983.

Biografía de Concepción Agramonte viuda de Sánchez (Homenaje Filial), 1919.

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García