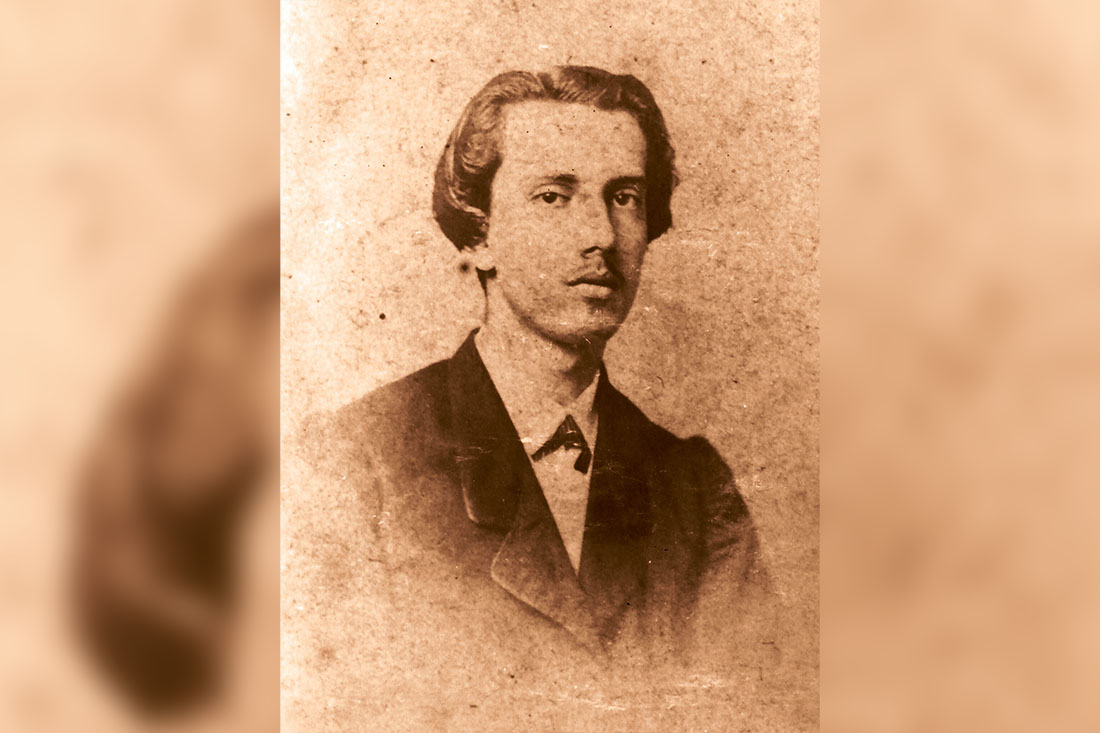

It was the people from Puerto Principe who built their own Agramontino myth. At a certain very singular juncture, the collective imagination, making use of its personal contours, turned it into a distinguished being, almost above the human raise. It is true that he did not lack personal attributes, or that the firstborn grew favored by objective family and social circumstances, and even warlike as to make him stand out his “military genius”, without having dedicated himself to the academy. It would seem that this historical subject gradually became a very singular being, looked at with a certain emphasis or pondering.

The curious legend of his probable rapprochement with the revolutionaries led by Joaquín de Agüero, shot by Spanish forces in Puerto Príncipe in 1851, seems to open the cycle of myths in the imaginary locals around Major Ignacio Agramonte.

Also when a close friend of the family alluded that as a child he felt great love for studies and was seen to be focused on reading books with great pleasure (is it that he shunned books for children, or did his parents provide him with only those who would lead him to be a remarkable human being?); or the passage of his compatriot Antonio Zambrana who emphasized that he had a thorough understanding of the problem that Cuba had to solve, in other words, that he was a forecaster of the free destiny of the Island; or Marti’s story taken from his countrymen when describing the entrance of the great lawyer in Court, causing astonishment due to his presence. Or myth built from the oligarchic ancestor of the first Agramonte, who had a Hispanic noble coat of arms. Or, moreover, for the unparalleled love sublimated between the lawyer and Simoni. The paradigmatic facts of his civil and military career. These are just some examples of the profile of the myth.

The myth in the epic feat

The Ten Years’ War began in the midst of the claim to constitute the national state. That was a juncture of full creation. The people from Camagüey would once again been reached with ponderous trims, perhaps because of his youth with which he challenged Spain at just 26 years of age, or because of his passion for civilism overflowing among the local patriotic nucleus. The truth is that his firm political stance and his rapture for finishing consolidating “his” army would make him contradict the first figure of the Republic and to challenge him to a duel.

At this point, his virile Man myth was reinforced again, and he was not messing around. His frenzy for his wife who was distant from him and for a beloved Cuba who had to be torn from Spain’s arms at any cost, made all the impulses of his soul overflow in him, the most sincere and purest. As when rescuing his friend Sanguily, who had been imprisoned by the Spanish, with only 35 of his brave men in front of 120 enemies. The fighting morale due to the success of the action and the myth of the warrior would continue to grow.

What force would stand in the way of that 31-year life cycle, which seemed untouchable as a demigod? Only death could interrupt him, at least momentarily, because even after he died in combat and his body was taken away, the myth would reinforce itself in the Camagüey imaginary; and it continues to feed every day with the contest of the history of the free and independent Cuban nation to which the mortal subject gave his love, his sacrifice and his life.

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García