By: Armando Pérez Padrón

Since the official birth of the cinematograph, on December 28th, 1895, the incipient creators of the future seventh art, fixed their attention on historical figures. The most significant case has been that of Jesus of Nazareth, embodied in the cinema from 1897 to 2010 in more than a hundred films.

In the first years of the arrival of the cinematograph in Cuba, the work of the father of Cuban cinematography stands out, Enrique Díaz Quesada, who directed seventeen of the forty fiction films that were shot between 1907 and 1922, and more than a dozen documentaries. , including two in our city: Panoramic Camagüey (1908) and The festivities of the Virgin of La Caridad in Camagüey city (1908).

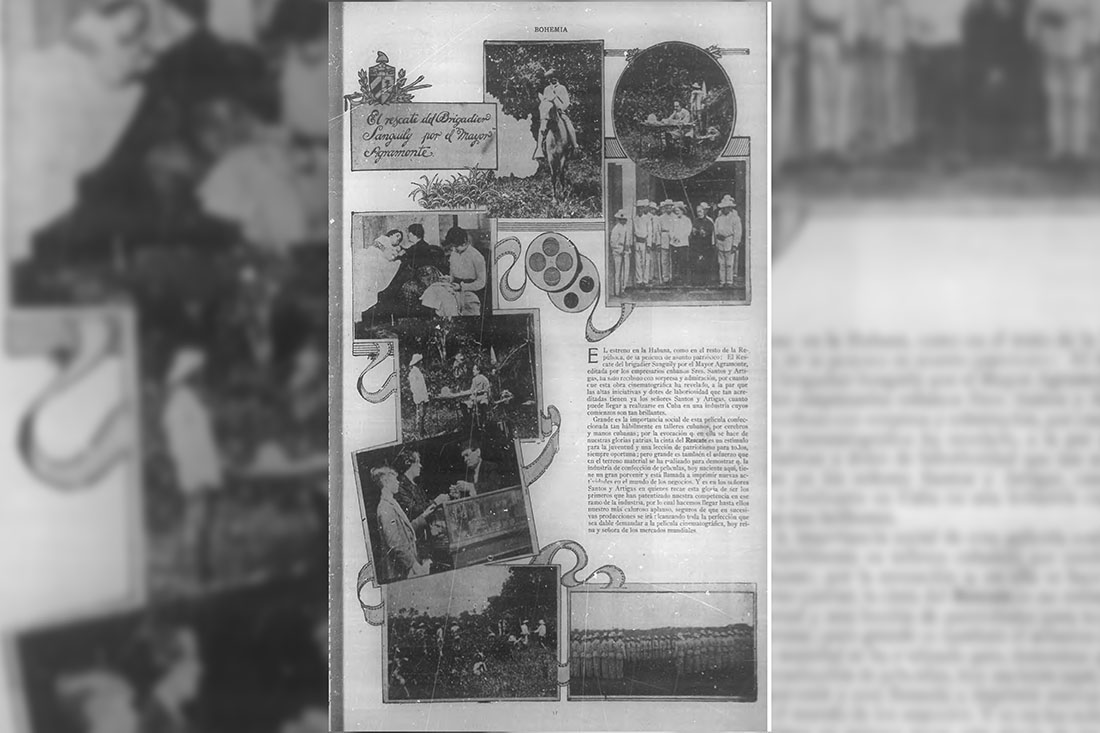

Meanwhile, one of the greatest events of our wars of independence was taken over and over again, physically or mentally, to our legendary city. This is how the filming project of The Rescue of Brigadier Sanguily was born, for which: “Enrique Díaz Quesada consulted the upright figure of Don Manuel Sanguily and discussed the matter with other men of the time, hence the authenticity of his film, which press points out and praises and about which authoritative people speak with praise. There are those who speak of an objective lesson, with estimable didactic values, useful for the use of our schools in teaching the history of the country and its leading figures.

The father of our cinematography, assisted by the journalist from Camagüey Eduardo Varela Zequeira, added to the script elements extracted from the story written by Manuel de la Cruz Fernández, in addition to consulting -as José Manuel Valdés Rodríguez stated in his chronicle- previously to Don Manuel Sanguily.

Thus, on May 12th, 1916, Enrique Díaz Quesada traveled to Camagüey to start filming. For greater authenticity of the story, Colonel Julio Sanguily -son of the brigadier- lent the prosthesis that his father used after the immobility of one of his legs due to a combat wound. For his part, the President of the Republic, Mario García Menocal, provided troops and equipment to help minimize the costs of the film and facilitate the completion of the work.

On December 23rd, 1916, a private exhibition was held at the Presidential Palace for the President of the Republic, who at the request of the producers sent them a letter on January 5th, 1917, in which he stated: “I take this opportunity to congratulate to you for the high degree of development that the printing of this film shows to have reached the cinematographic art in Cuba, as well as the correctness of the theme that has served as an argument and that will surely revive, in our youth, the feeling of nationality, which is the primary basis on which the future of the republic rests.

Seventeen days later it premiered at the Payret Theater. Many chroniclers and witnesses of that moment had words of praise for the film. José Manuel Valdés-Rodríguez overflows with enthusiasm in his review: “On celluloid, the Creole savannah encouraged, and the mambí machete shone in the morning. The Creole Bayardo and his centaurs put the Cuban halls on their feet, when it was already fashionable to ignore our affairs except to clear and burn the incredible forests of that same legendary Camagüey and sow the provid land with cane.

Valdés – Rodríguez adds one more quality to the film story: the work’s ability to alert and remind forgetful premature babies, how much blood was shed, and how many young people, and sons of the Homeland and of humanity offered their lives for a Cuba that It was not exactly the one that manifested itself in those days.

An anonymous critic expressed convincingly: “The strictest truth is admired throughout the film, since that has been the commitment of its editors, who do not cease in their intentions of transferring valuable pages of our history to the cinema without paying attention to sacrifices.”

105 years after what for many constituted the most reckless war action of the Ten Years’ War was taken to celluloid, El Mayor’s cry of shame rises above any type of merriment to remind us of what Valdés – Rodríguez wisely sentenced: “The Creole Bayardo and his centaurs put the Cuban theaters on their feet, when it was already fashionable to ignore what was ours.”

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García