Perhaps the street vendors of the newspaper El Camagüeyano announced, on March 25th, 1924, –one hundred years ago– that a certain Interino took over the Pisto Manchego section from that day on.

Interim, was the pseudonym that a thin mulatto with straight hair and about to turn 22 years old assumed for that space: Nicolás Guillén Batista from Camagüey; many years later recognized as the National Poet of Cuba.

His father, Nicolás Guillén, was a journalist, and his son also embraced the profession, which he cultivated almost until his death in 1989.

To leave no doubt about his vocation in this regard, he proclaimed: “I have said it many times: I am a journalist, and also a poet.”

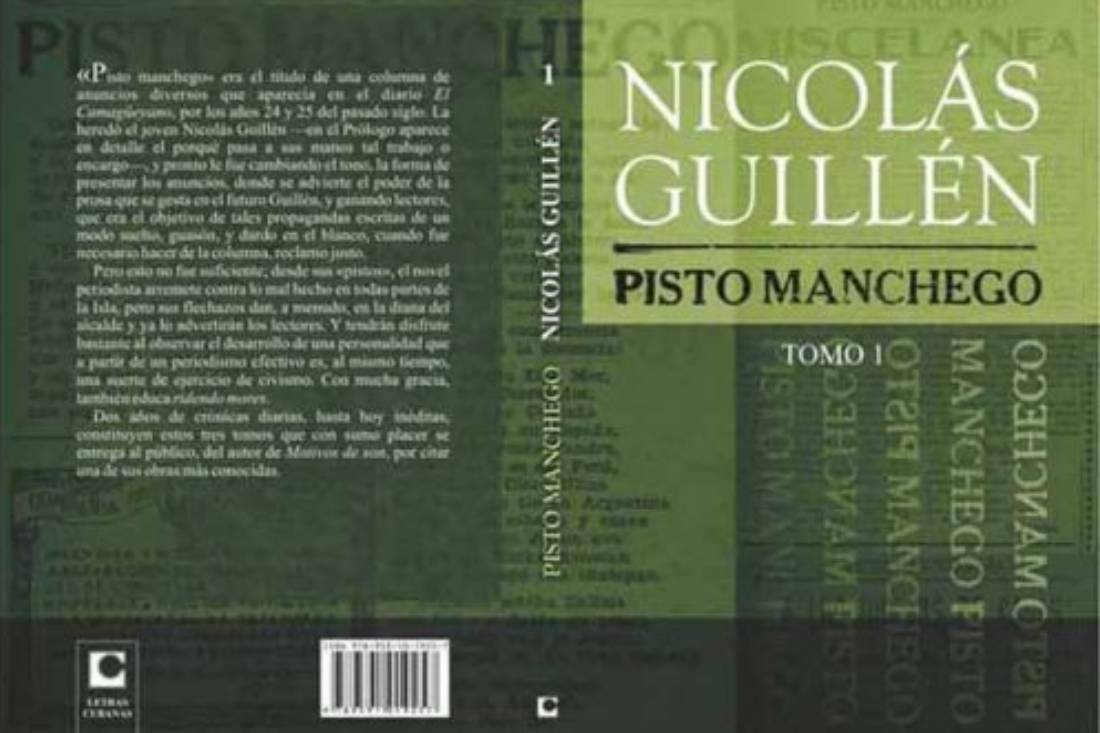

He took over the writing of Pisto Manchego – the name of a Hispanic dish with a variety of products – replacing the Spanish Santoveña, and with his talent he gave it a higher hierarchy.

The section was characterized by combining journalistic information with advertising, which was very unique, since both topics are usually published separately.

Guillén used the journalistic technique in the section, not only in a quantitatively broader way, but with more depth and variety, in line with giving greater importance to the news content of the column.

The recipients were informed, in the context of journalism, of matters of great local, national and international interest, while they contacted a context in which they could find satisfaction for their needs for material goods and services; this must have had a positive influence on the increase in sales.

Applied with an effective impact on communication, due to its simplicity of lineage, the aforementioned convergence worked through a pleasant style and positive values of the content and form of writing, seasoned by Creole choteo; which at that time had a strong content, in texts and caricatures in the press media.

Likewise, he used customs, which contributed to reinforcing communicative power.

He used, although partially, poetry in a humorous tone to expose commercial advertisements, which additionally provokes enjoyment of rhyme. This reminds us, but with differences, of those rhymed street proclamations that have practically disappeared.

Advertising, in the section of the aforementioned space, denotes a simple use, without complex formulas, with very synthetic references, dependent on the news core.

These advertisements also reveal historical data, among them, that four of the commercial establishments mentioned 100 years ago in Pisto Manchego still exist in the capital of Camagüey: Casa Casildo, La Gran Señora, La Palma (formerly El Colmado de La Palma) and La Espiga of gold.

The journalistic materials addressed by Guillén insert a notable heterogeneity of facets, such as those corresponding to social, economic, political, cultural and sports issues.

In this regard, he used the informational values: prominence, closeness, impact, human interest and curiosity; through the use of the chronicle, the most personal of journalistic genres and which has a wide capacity to penetrate the recipient.

Although the contents are distant in time, his chronicle texts are not technically archaic, but appear to have been completed today.

Among these structural characteristics are the suggested opinions, without an editorial tone, elevated language, but without baroque and understandable for a heterogeneous public, stylistic freedom subject to the mandate of the news, direct style, indistinct use of the chronological story or not, and subordination of the judgments and interpretations to the narration of events and the presentation of data.

Nicolás Guillén’s presence in Pisto Manchego ended on August 30th, 1925, after publishing more than 400 chronicles in El Camagüeyano, then the main newspaper in the province of Camagüey and one of the most important in the interior of the country.

(Based on a degree thesis project written by the author for a Master’s Degree in Communication Sciences).

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García