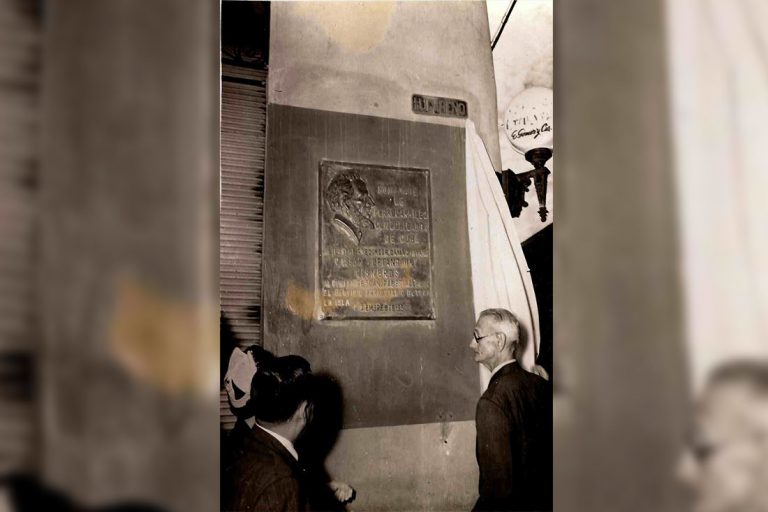

On Lugareño street, on the corner of Hermanos Agüero, before Contaduría and San Ignacio, a bronze plaque marks the place where he was born on April 29th, 1803; Gaspar Alonso Betancourt Cisneros, “El Lugareño”, to a wealthy family.

At home he discovered the world of letters. Child of prodigious intelligence, cultivated by the dedication of his parents, Diego Antonio Betancourt Aróstegui and Loreto Cisneros y Betancourt, El Lugareño would make reference about them in a letter to his friend Count Pozos Dulce:

“My father was a gentleman, educated in the old way and by means of the resources that were available at that time for this purpose in the east part of the Island, where there were no schools, nor regular public schools and the entire education system constituted in much prayer and little writing, no spelling, parrot grammar and arithmetic on the floor. So my father, despite belonging to the highest class of Camagüey society and having been born a mayorazgo, it can be said that he knew charitably speaking, how to pray and speak well with some fluency and little spelling and count to the first four rules.”

“My mother had the heart of a Spartan. The generosity of her character and her truly Christian charity recognized no limits other than those of her power and faculties, and even these exceeded the force of her will. Her understanding was clear, she was good at anything: in another country, or at another time, she would have been a woman as distinguished by her talents as by her virtues. Overcoming the concerns of her time, she did not need a teacher to learn how to write, which was then considered in Camagüey as sinful for women, (…). I read a lot about her and perhaps she had more books than all the other ladies from Camagüey of her time”.

He studied in Camagüey until 1822, the year in which he was sent to the United States of America to complete his training, settling in the city of Philadelphia, his date of arrival in the northern country has been the object of contradictions indistinctly: Federico de Córdova, Manuel de la Cruz and Fermín Peraza, indicate the year 1822 as the date of his departure; while Jorge Juárez Cano, Liliam María Aróstegui Aróstegui, Rafael Rojas, Fernando Crespo Baró, mark the event in the following year.

In this city he would attend regularly to the gatherings of his relative Don Bernabé Sánchez, in them he meets the Argentine José Antonio Miralla, makes friends with Vicente Rocafuerte, who became president of the Republic of Ecuador, with the Peruvian Don Manuel de Vidaurre , who held the position of Oidor of the Audiencia of Port-au-Prince and later President of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Republic of Peru; and with the Cuban José Antonio Saco among others.

Discovery

These meetings mean for El Lugareño in this period the center of his instruction, referring to them, in a letter to his friend Domingo Del Monte he expresses that he “heard, learned and kept silent.” During these years, Cubans, mainly from Camagüey, were arriving in Philadelphia, persecuted by the colony government for the crime of constitutionalism, and the gatherings naturally became a meeting of conspirators against the Spanish colonial rule in Cuba; and in which the names of Bolívar, Sucre, Páez and others resounded, screaming for independence.

Here the convictions of a convinced, determined and unshakable separatist were forged in Gaspar Betancourt. For this reason, despite his youth, he was chosen to form part of the commission that on October 23rd, 1823 left New York, on the schooner Midas, bound for La Guaira, Venezuela; to meet with Simón Bolívar, in order to promote an insurrectional movement in Cuba.

The protagonists

The delegation was made up of José Antonio Miralla, Gaspar Betancourt Cisneros, Fructuoso del Castillo, José Ramón Betancourt and José Agustín Arango, and José Aniceto Iznaga from Trinidad.

In Venezuela they could not make contact with the Liberator, still busy in the founding of five nations, but with General Antonio Valero, a native of the island of Puerto Rico; which pledged with the Cuban patriots to take a personal interest in Bolívar in favor of liberating Cuba from Spanish colonial rule.

After twelve years in the United States, he returned to Cuba in 1834, and quickly took on the task of applying all the knowledge and experiences, betting on the economic and social progress of his region of origin and his illusion in the future of the Great Antilla and America against the antiquity of Europe and especially Spain.

The education of the people, including the marginalized sectors, had a place in his work. His passion for matters related to them can be seen, his participation with interest in the sections of the Patriotic Society devoted to examinations; he also criticized the traditional teaching methods “where you learn everything by heart according to the book.”

Work

He dabbled in Comparative Pedagogy. He drew up a school regulation that, due to its characteristics, was far superior to those of the time. On his vast estates in Najasa and Horcón he literate the peasants who lived on his estates and created schools to educate their children where education and teaching methods that humiliated children were absent.

His criticisms and proposals were collected in his traditional articles “Everyday Scenes” appeared in the newspaper “La Gaceta de Puerto Príncipe”, on how to develop the teaching of natural sciences.

In the 1945 book “History of Pedagogy in Cuba” by Emma Pérez, the author makes a comparison between the work of the Camaguey and that carried out by José de la Luz y Caballero in Havana, the Guiteras brothers in Matanzas and Sagarra in Santiago of Cuba, although the latter managed to specify a better pedagogical work.

For Gaspar Betancourt Cisneros, his ideas of progress join the best tradition illustrated with utilitarianism, assimilated during his early stay in the United States. “The true progressive must be consistent with his principles: never go backwards; to stop, never; to advance, always (…), the mission of the progressive is to advance and improve ”.

Concerns of El Lugareño

Among all the progress seen, the one that most caught his attention was the railroad.

Santa María del Puerto del Príncipe was the third most populated city on the island. Livestock, traditional crops of the country, sugar cane and coffee, constituted the fundamental lines of the Camagüey economy, where its mills could not compete with the large factories from the western region of the country. Trade despite the existence of the ports of Nuevitas and the southern one of Santa Cruz del Sur; they could not get out of their isolation and delay.

Hence his obsession with covering railroads since his arrival in the country, as a stimulus for economic development in the central-eastern region of Cuba, which would allow trade in Camagüey to be removed from its isolation.

On November 26th, 1836, El Lugareño, guardian of the company, presented the request for the construction of a railway between Nuevitas and Puerto Principe to the landowners Luis Loret de Mola and Tomas Pío Betancourt,.

On January 10th, 1937, Captain General Miguel de Tacón granted the concession, this being the second approved in the country for its construction. This same day the Nuevitas-Puerto Príncipe Railway Company was established.

It is striking that a company so advantageous for the region experienced various troubles, did not have the full support of the regional wealthy families, Betancour Cisneros paid for the first studies carried out by engineers Benjamin H. Wright and Eduardo Huntington on the survey and contour of the land by where the iron road should be, completed on March 15th, 1937.

The first rails began to be installed in February 1841 and a year later in March 1842 El Lugareño gathered in Nuevitas a group of high society from Camaguey to travel the 4 miles completed.

The years would pass until April 5th, 1846, in which the first section between Nuevitas and O’Donnell’s whereabouts in Sabana Nueva would be concluded and finally inaugurated on December 25th, 1850; works that he would not see culminated when he was exiled from Cuba for participating in the heated political arenas of his time.

He erred, yes, like other heroes of those years. Towards 1845, the idea of incorporating Cuba into the United States would be for the Cuban landowners as a lifeline, so that until ten years later it was the political attitude that prevailed among them.

The cause that determined this tendency was panic or an imminent bankruptcy of sugar production as a result of Spanish intransigence about granting reforms that would promote the development of that industry.

In 1856, he abandoned the annexationist position when he saw that the only solution for Cuba is the path of revolution to achieve independence. On July 7th, 1861, when he was granted amnesty, he returned to his homeland.

On February 7th, 1866, El Lugareño died in Havana; a halo of sadness ran through the streets of the capital of Cuba, the news spread among the neighbors.

The supporters of the Metropolis were surprised by the sea of people that attended the funeral only compared to those of four years before at the funeral of José de la Luz y Caballero, summoned by love, respect and admiration for his person.

Gaspar Betancourt Cisneros was a fervent fighter against the slave trade, vigorously opposed against the slavocracy, a term used by him to define the survival of an institution that turned the Cuban ruling classes themselves into slaves “slaves for having slaves” such as emphasized in his fine Creole irony. He believed in the promotion of white colonization, an action that he practiced on his properties with Canarians.

He was split between annexation and independence but the independence movement in his mind defeated the mainstream during the forties and part of the fifties of the Cuban XIX century.

Francisco Calcagno wrote a brilliant obituary for the newspaper El Siglo that did not publish it, but edited it later in his valuable text, Cuban Biographical Dictionary:

“A man has just died in Havana whose life, consecrated to the service of the soil that saw him born, will leave an imperishable memory in our Cuban hearts; a man who was for Camagüey what Arango and Parreño were for Havana, a man whose history will pass unscathed to posterity, to receive in it as many blessings as tears the grateful homeland gives him today.”

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García