Let’s put aside, for now, the Triangular Chain of Puerto Príncipe in the glorious decade of 1820. To be honest, it was responsible for politically shaking the undemocratic government structures for bringing the Bolivarian liberation option closer and thus promoting an uprising, coordinated in the West with the organization secret Soles y Rayos de Bolívar led by Venezuelans, Ecuadorians, Colombians and Cubans.

Towards other regions of the Greater Antilles, both associations extended their projects. Santi Spíritus, one of the first to know it, also spread to Bayamo and Santiago de Cuba. They sought to coordinate plans, joined by the Spanish military and members of the civic militias who did not hide their discontent with the Old Regime.

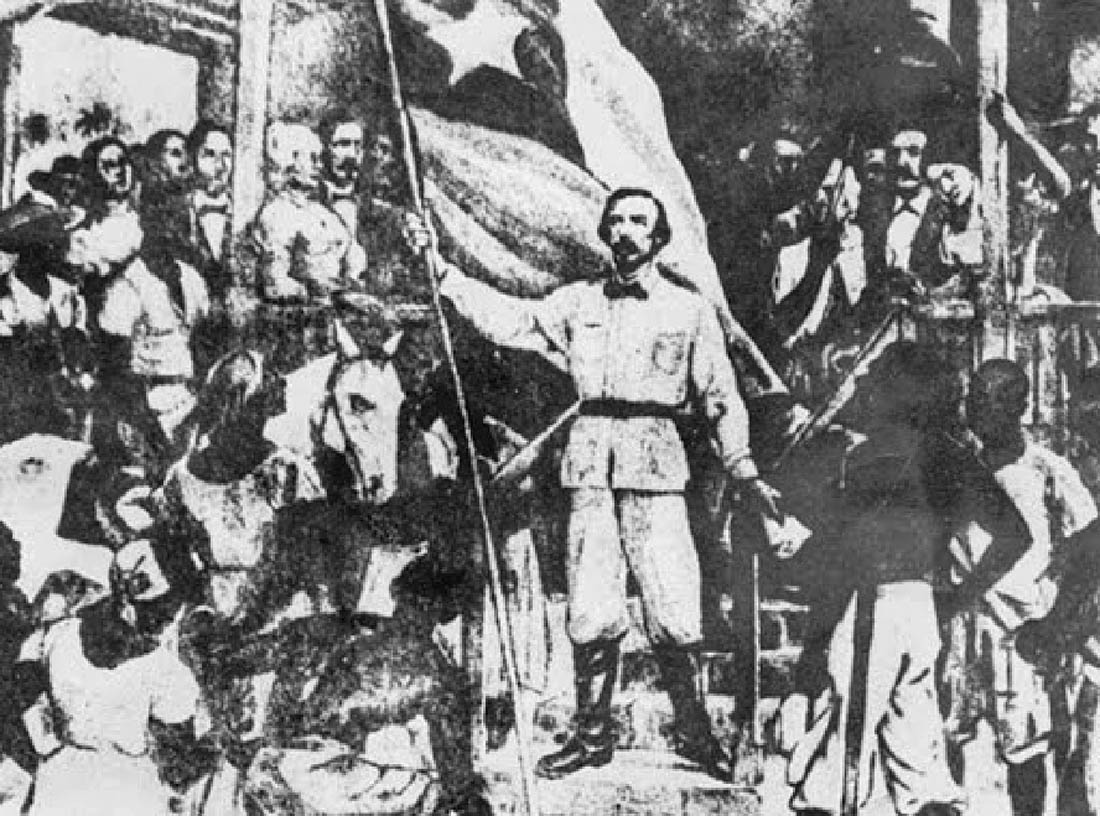

Preamble to the 1868 Revolution

An outbreak of political resonance took place in Puerto Príncipe in 1841, when a handful of young followers of the Bolivarian ideological thinking staged a social outbreak in the Philharmonic, which transcended the Plaza de Armas and the town hall servile to the Hispanic crown. The surnames Agüero, Arango, Cisneros, Montejo, Piña, Recio, among others, tell us about the family origin and political commitment of these «enlightened».

Almost twenty years later, in 1866, another outbreak returned to shake the city high school. Was it a coincidence that the surnames were similar to those mentioned above? The Arango brothers in the front line of combat, Varona Borrero, Cisneros Betancourt (greater coincidence?)… The details of the Conspiracy of the Caleseros that had been led by Bernabé de Varona Borrero (Bembeta), the same one that caused the clash between the militaryand civilians at the high school were still fresh (another coincidence?).

The situation on October 10th

Augusto Arango y Agüero and Salvador Cisneros traveled to Las Tunas to the Muñoz farm, in September 1868, to the conspiratorial meeting with eastern patriots responsible for starting the uprising. Back in Puerto Príncipe, Arango and his brother Napoleon took up the arms of the Philharmonic, which the former kept in his house in Soledad Street no. 16, and on October 11th he went to visit the ranches to add men to the insurgent group.

The first of those surprised by the Oriental outbreak was Governor Julián de Mena and the military body. It can be affirmed that although somewhat uncoordinated by the Cespedista movement, and Camagüey was surprised by the shift in the date of the uprising that Carlos Manuel de Céspedes was supposed to carry out, yet almost a month later Arango and his troops took the garrison of Guáimaro; on the 11th, San Miguel de Nuevitas and El Bagá fell into his power.

Meanwhile, on November 4th, 76 patriots had risen with weapons on their shoulders in Paso del Saramaguacán. On the 5th Cisneros left for the battlefield; on the 11th Ignacio Agramonte and his brother Enrique entered the military scene. On November 26th, Arango assumed the leadership of Camagüey. The accumulated history had caused the uprising to be carried out to support those in the East.

Manuel de Quesada Loynaz

Historiography deserves to trace the insurrectionary antecedents of this man from Puerto Príncipe who fought in Mexico and gained experience and military rank, which upon his return to Camagüey earned him the right to carry out an anti-colonial struggle. Well, it turns out that General Quesada was the instigator of an armed uprising in his hometown in 1866. Did those from the East and the poet and patriot Francisco Muñoz Rubalcaba know that he was visiting Camagüey to assess the political situation? Again, coincidence? Perhaps the revolutionary fervor was connected with the Conspiracy of the Caleseros and with the brave ones at the high school? There are still too much things that need to be clarified about the struggles.

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García