Teaching is fertilizing. I do not want sponge brains or granite brains before me; if not that they embed ideas and transform them.

Enrique Jose Varona

The first values of the philosopher, psychologist, journalist, literary, linguist, Doctor of Philosophy and Letters, honorary president of the Academy of History and member of the Academy of Arts and Letters; Enrique José Varona de la Pera, I discovered them with the study of the compendium “From my belvedere”, a text from 1907. I was far from interpreting the cultural magnitude of a work, in which few historians have stopped to evaluate the sociocultural portrait it makes of Cuba, who perceived the role of cultural identity as a process of self-awareness beyond the individual, to make it visible as a nation.

Later, my modest knowledge would progress with other texts of his that move through various fields, from ethical-moral to historical lessons; all characterized by the sagacity of language and his keen observations. The reflections of doctors Luis Álvarez and María Antonia Borroto also invited me to rethink this man’s work, -extensive and insufficiently studied- a man with political positions that contrast with each other, in the middle of two defining, complex and dynamic centuries for Cuba : the formation of the national identity in the 19th century until the revolutionary effervescence of the 1920s.

His work: thought and context

Varona shows his intelligence, language skills, and cultural sensitivity early. At 18 he won the contest dedicated to the leading figure of El Lugareño and was a regular participant in the social gatherings of the Santa Cecilia Popular Society. In 1868 he joined the independence struggle, which he left prematurely and later assumed a position contrary to emancipation and joined the autonomist party until 1886, when he retired from it.

During the preparation of the necessary war, he returned to the independence struggle, with a responsibility reflected in “Two voices in the shadow”, a blow to the adolescent creation, “the prodigal daughter” that received much criticism during his life for the Spanishizing intention, without their detractors questioning how many Cubans were independentists without having previously supported other ideological currents; nuances of the formation process of national identity, which on several occasions is intended to be ignored or decontextualized.

His relationship with José Martí runs between the intellectual and political interests they share. In 1895 in New York, after the death of the Apostle, Varona succeeded him in the direction of the newspaper Patria.

In the North American intervention he was Secretary of Finance and Public Instruction, in the convulsed Neocolonial Republic he served as vice president from 1913-1917, to later retire from the public life, a circumstance that does not prevent him from opening the doors of his house to the new generation. Together with them he founded the Federation of University Students and lashed out at the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, convinced, in his own words, that “a Republican Cuba looks like the twin sister of a colonial Cuba.”

Varona the pedagogue

As a pedagogue, he showed an exceptional ability to warn of the need for immediate changes in education, a task known as the Varona Plan. Its reforms promoted teaching with the perspective of guaranteeing professional competence at each level and with it an integrated teaching process, supported by modern and scientific resources and values.

Varona conceives the creation of the Pedagogical School not only with the intention of training teachers, but also with the success of guaranteeing scientific research on teaching problems. The renovating work in the educational field and his exalted teaching made him, in the words of Merardo Vitier, a “Teacher of youth”, or a “Teacher of Cuba” according to Pedro Henríquez Ureña. These criteria make us debtors of Varona, not with monuments or slogans, but in the creative practice of teaching.

A life of contrasts and successes

Enrique José Varona died in Havana on November 19th, 1933. His funeral was accompanied by young people, who despite his advanced age took him as an imperishable symbol. His remains were mourned in the assembly hall of the University of Havana, a place where admiration and pain were combined in a passionate speech, offered by Raúl Roa. Once again, questions remain that we must ask: What services did the Cuban intellectual who made him,in his eighties, a representative of the renewing, audacious and revolutionary youth force of a society rendered to the Homeland?

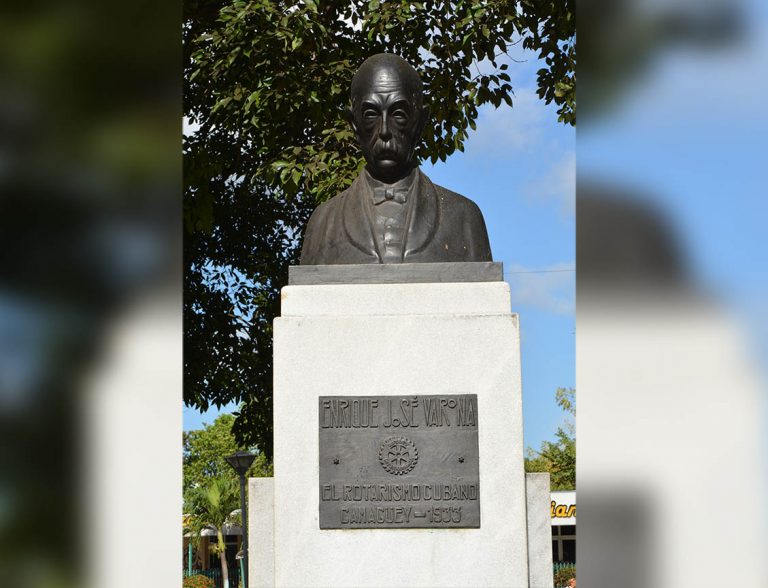

The answers can only be found when we reveal his life and work, full of contrasts and successes. The people of Camagüey owe more study to their texts, greater promotion of their work, inside and outside the classroom. Few know that the popular artery of San Ramón, since January 30th, 1899 at the proposal of the City Council, bears his name. Neither is well known that a plaque on Lugareño Street marks his birthplace, or that in one of the most important parks in the city there is a modest bust by Fernando Boada, made for the Centennial of his birth.

Fighting against the oblivion of great men will always be a responsibility and an honor.

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García