On February 26th, 1869, the Assembly of Representatives of the Central Region was held in Camagüey, and one of its agreements was the abolition of slavery. Seen this way, five months after the war for independence began, the problem of slavery and its abolition was present from the beginning.

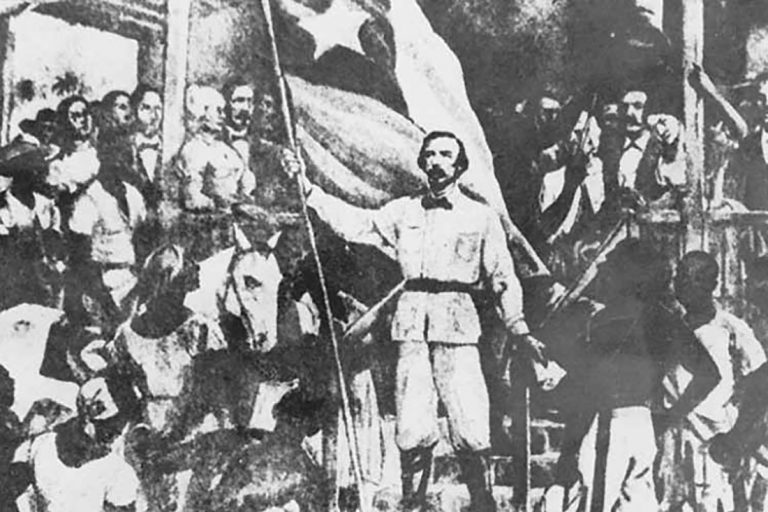

On October 10th, 1868, the bell of La Demajagua sugar mill rang at dawn calling for the everyone, this time its sound representing the beginning of the daily tasks as usual was different. In that place together with its owner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes were several of the conspirators against the Spanish power in the region. The bell announced the beginning of the struggle to put an end to the colonial regime of the island and to slavery, thus initiating the liberation of Cuba.

At mid-morning, Céspedes gathered about twenty slaves of the 53 who were in the mill when he acquired it, set them free and invited them, if they wished, to conquer freedom, since Cuba needed all its children to achieve its independence. The same did the followers who accompanied him, with theirs. Thus a sugar mill owner, ranchers, landowners, lawyers came together with their former slaves in the long run without imagining it on the way to independence.

In the “Manifesto of the Revolutionary Council of the Island of Cuba” on October 10th, among the reasons why they went to war; they declared gradual emancipation and compensation from slavery. That the manifesto promulgated about abolition is no accident. In the Minutes of the Rosary resulting from the agreements reached at the meeting held at the Rosario mill on October 6th, it was explained that “We want to abolish slavery by compensating those who are affected.”

At another time on the 28th of the month Bayamo, in the power of the liberating forces since the 20th; The two councilors of the town Ramón de Céspedes and José Joaquín Palma had agreed to the motion after extensive debates to demand the immediate abolition of slavery. In this regard, Palma stated: “If in slave Cuba there could be no free men, in free Cuba there can be no male slaves”. A day later Céspedes issued an order by which the admission of slaves into the army was forbidden, if it was not with the consent of their owners. We can see this order as counterproductive to what was expressed on October 10th, in the just started fight, it could not have as enemies the Cuban slave owners who had not yet joined the revolution.

From different angles

The greatest advance on abolitionism within the libertarian process goes hand in hand with the military actions and is gradually becoming radical as well. On December 27th, 1868, the decree on the abolition of slavery was promulgated, it would be the most far-reaching but with its limitations on the subject, such as that it declared the slaves presented by their owners to the military chiefs free and that in the future they would receive compensation.

The decree stipulated that pro-independence Cubans would have their property respected as well as neutral Spaniards. It only declared free the slaves owned by the enemies of the independence cause, and they were not entitled to compensation. In it a discordant point is appreciated when expressing that the owners, who provided their slaves to the fight, would retain their property, as long as the issue of slavery was not resolved, in general the decree was not the intended Universal emancipation.

The handling of abolition through decree in the first months of the war was strategic. With it, it was the possible the participation of western landowners in the fight, causing fear in a wide sector of whites, not only among owners due to the weight of the black population of this region, that could unleash a race war.

From what was stated in La Demajagua Manifesto to the decree on abolition, things did not turn out so great for Céspedes. For him, the bayames was in the dramatic position that made him be really careful and seek possible conciliations of the different mediate and immediate factors.

By his revolutionary position he pronounced emancipation, but as a revolutionary statesman he had to calculate what in the short term was profitable to the cause of the revolution. These affirmations were exposed in the letter that Céspedes sent to the president of Chile on December 9th, where he expressed: “We have only respected, although with pain in our hearts because we are staunch abolitionists, the emancipation of slaves, because it is a social matter of great importance, that we cannot solve slightly, nor interfere in politics because it could pose serious obstacles to our revolution.

The liberation of the slaves included in the decree and the single command problem had been widely debated by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and Ignacio Agramonte and Ignacio Mora, together as delegates of the Assembly of the Central Region.

The month of February 1869 brought two notable events for the independence struggle, the armed uprising of Las Villas and the proclamation of the Camagüey decree on the abolition of slavery.

A human achievement in the middle of the fight

On February 26th, 1869, when the Representative Assembly of the Central Region was constituted, its five members issued their own decree to abolish slavery. For the Liberal Democrats of Camagüey, the conditions of slavery in their region allowed them to adopt a more radical position than that of those of the Western Region. It was the answer to Cespedes’ provisions on the emancipation of slaves, considered by them as very moderate. It was the form through which they could make possible the incorporation of the slaves to the fight.

For the people of Camagüey, the abolition had to be established completely, immediately and universally. It foresaw compensation at the most opportune moment. And that capable slaves were obliged to perform military service, and those who for some reason could not do it, had to continue working during the war. The assembly warned that the obligations established in the abolitionist decree were equal to those imposed on free men, due to the duty of all to contribute to the freedom of the homeland.

For the men who followed the independence idea of 68, decreeing the abolition of slavery made them philanthropists, but making them their equals made them revolutionaries. To do this, the first thing was to win the war, as an expression of a revolution in progress. Without victory there was no abolition.

These first abolitionist attempts within the War of 68 actually tried and in a historically short term to solve a problem of centuries, while trying to avoid the deep political problems that in the conjunction of the different interests bring these measures to the revolution.

With the abolition of slavery in the early moments of the fight, it also responded to the risk that Spain would take the lead and declare the total abolition, and with it launch the endowments against them, being able to repeat the history of Boves in Venezuela. From the Spanish Constituent Courts themselves, abolitionist voices of federalist republican deputies were raised, demanding that the immoral institution of slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico be extinguished forever.

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García