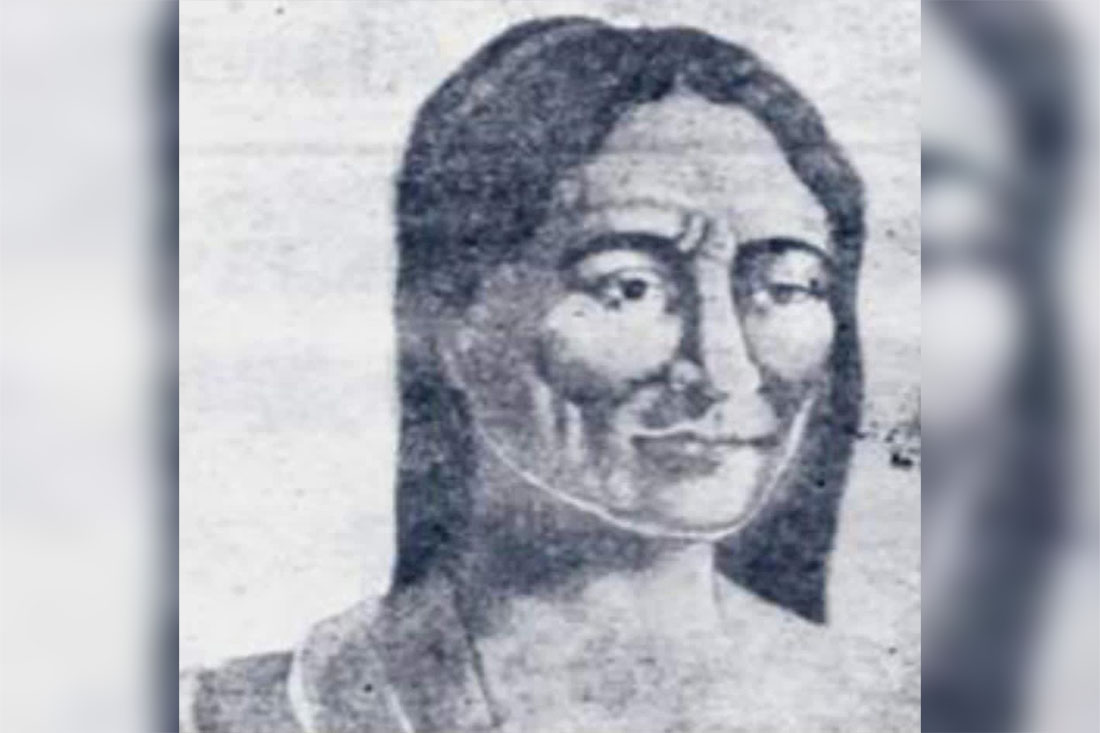

Legend has it that, in 1800, a character from Puerto Príncipe spread panic in the former town of more than 336,777 inhabitants, the individual whose name was never known, was described as a corpulent man, with enormous strength, distro in the handling of the bow and arrow and a primitive cruelty, reflected in the singular fact of feeding on the tongues of cattle. Qualities that together with his physical description earned him the nickname of Brave Indian.

Hence, these qualifiers refer us to a first unknown; his appearance was really that of an Indian, or the social elite of those years simply wanted to associate his misdeeds as a bandit with those first inhabitants of the region in a discriminatory position that sought to punish the Indians who survived the barbarities of the conquerors.

Although the details of the legend collected by Tomás Pío Betancourt, Juan Torres Lasqueti, Jorge Juárez Cano, among others and closer in time Héctor Juárez and Roberto Méndez, nourished by bibliographic reviews and information from the chapter acts, do not precisely establish the outrages of the “brave Indian”, the scope that the rumor of his felonies had in his time is unquestionable.

The fear around his figure

The fear in the city due to the presence of the malefactor identified as a cannibal who stole children sealed the fate of the character and made the City Hall in 1801 offer the substantial reward of 500 to whoever managed to arrest him, a second question arises ¿With this type of outrages, why no information was recorded in the City Hall of the vandalism perpetrated by the Brave Indian to support the efforts of the authorities?

And on the other hand, the inescapable questions, if the subject’s excesses were such, why did three years pass before he was arrested? Fear, little importance for the town or simply disproportionate rumours?

Without conclusive answers due to the lack of reliable files among the families of the of Puerto Príncipe and the brief information of the chapter minutes of the City Council in these years about the events, it is known that the bandit was finally captured and killed on June 11th, 1804 by the residents of the Cabeza de Vaca farm, Don Serapio de Céspedes and Don Agustín Arias, in the offensive to recover the kidnapped José María Álvarez González.

And again, another conjecture surrounds the legend, when it is believed that it was a slave of Don Serapio who captured him, but due to his condition he did not have the right to collect the reward that the illustrious neighbors obtained on July 2nd of that year.

The answers are immersed in the field of speculation or the nuances that accompany each legend, the truth is that the body was exposed at midnight that day in the Main Square, between the curious gaze of the residents who approached and the untimely noise of the bells that proclaimed his capture.

Legend has it that many neighbors went to the churches to thank the answer to their prayers to be freed from that bandit, while others celebrated that collective triumph in the traditional San Juan festivities.

But history does not allow forgetfulness and in 1893, a pro-independence newspaper circulated clandestinely bearing his name, which leads you to wonder if the Brave Indian was just a symbol of banditry or also of rebellion.

The tradition…

The poet Miguel Unamuno expressed that the “Base of the collective personality of a people is tradition”, wise words that appear in the prologue of the book El Camagüey Legendario and that each one makes his own when the twists and turns of history are interwoven with fiction to through the legends remember sad, singular, laughable or simply inexplicable events.

For this reason, I invite you to visit the Park of Legends located on República Street near Plazuela del Puente, where the murals of plastic artist Joel Jover engraved on ceramics offer you some legends that accompany the history of this ancient city. In the near future our children and grandchildren will also register those who complement the cultural memory of contemporary Camagüey.

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García