No major political influence of reforms in government structures had the historic region of Puerto Príncipe in the first half of the nineteenth century as the creation of the Royal High Court of San Domingo, at the same time, which would have an adverse impact on the mentalities of some of the Creole members of the town hall, most of whom are defenders of the Old Regime, but to a greater extent among the powerful Creole hatera oligarchy.

The town hall / court conflict

The differences between the members of one and other corporations would begin to be noticed shortly, as some said the council seemed to ally the most recalcitrant Goths or servile fundamentalists, such as the new Count of Villamar Santiago Hernández y Rivadeneyra who refused to accept free elections of the consistory, for fear of supporters of liberalism. On the other hand, the audience was lined with several of the “feverish heads” followers of freedoms and the most advanced ideas in the world.

So that after the creation of the court in the town of Puerto Príncipe, nowadays Camagüey city, in June 1800, the liberal-democratic option would gain momentum to campaign against absolutism, social and political stagnation; a position incompatible with the libertarian options that would open up on the continent with the start of the emancipation struggles promoted by Bolívar. The hopeful air could not be more favorable for the removal of the pillars of the old colonial society.

The ongoing revolution

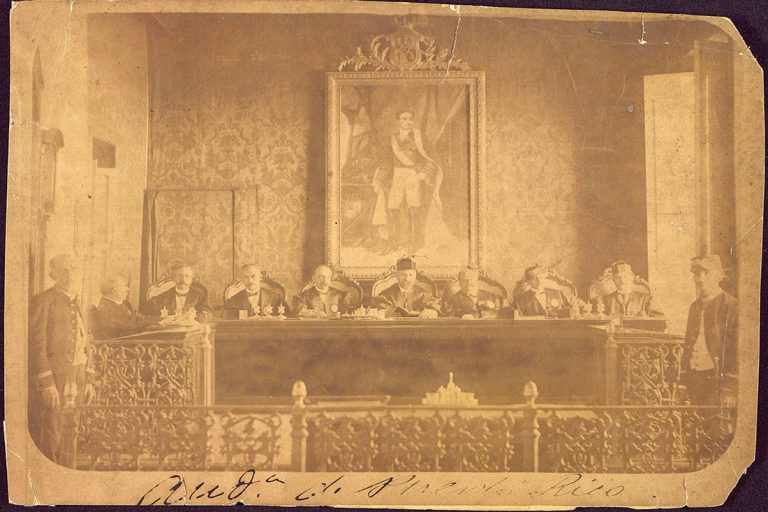

Puerto Príncipe would become the center of judicial, criminal and civil decisions in the Greater Antilles, which in turn would have an impact on its political environment. We must not lose sight of this important issue, among other reasons, because the administration of justice would cease to be an attribution of the mayors at the same time that the Captain and Governor and the Captain General would also be relieved of that duty, which would mean in practice, the “rebellious and dissolute” principeños of the all-encompassing central power could separate themselves as much as they could, and would look for a propitious occasion to dissent from the superior government of the Island.

It should be noted that the court would be the only entity of its kind until 1838, when the Praetorial of Havana was founded, which would have influence as far as Remedios, Sancti Spíritus, Trinidad, Holguín, Manzanillo, Santiago de Cuba and Baracoa, which it is not small thing, if we take into consideration to what extent the prinicpeños would be able to make their political influence extensive and effective in the event that an anti-colonial outbreak started in Cuba.

In a similar way, the liberal-democrats in the court would play a significant role in outspoken opposition to the Old Regime. This would be corroborated in the 1820s in the midst of the creation of revolutionary meetings to promote a generalized insurrection with the support of Bolívar. Therefore, it would not be by chance that the authorities pointed out that the Royal Court “had concentrated a privileged number of enlightened people, bearers of liberal ideas from the insurrectionary provinces of Latin America […]”. Indeed, it was the moment used by several of his lawyers to try to storm the sky and demolish the archaic structures of absolute power on the Island.

And if that period failed due to internal and external causes, which need not be addressed here, however, the radical thinking achieved up to that point was not in vain, nor was the joint effort of many to remove the old structures of power. And we already know that among some of those with the same surname who made up said legal entity, but with greater audacity and courage than they, the upright jurist Ignacio Agramonte y Loynaz would be at the revolutionary vanguard in a new political situation, who would give impetus to the liberating revolution that would accompany the lawyer from Bayamo Carlos Manuel de Céspedes to, together, carry out the project of a free nation attached to laws and rights.

Translated by: Aileen Álvarez García